2 Week 1

2.1 Week 1 Learning objectives

At the end of this lesson you will:

- Be able to define data science and advanced data science

- Be able to define the types of data analytic questions

- Be able to follow a data analysis rubric to evaluate an analysis

2.2 What is advanced data science anyway?

2.2.1 Maybe we should start by defining data science….

Before we can define advanced data science we need to define data science. The definition we will use is:

Data science is the process of formulating a quantitative question that can be answered with data, collecting and cleaning the data, analyzing the data, and communicating the answer to the question to a relevant audience.

In general the data science process is iterative and the different components blend together a little bit. But for simplicity lets discretize the tasks into the following 7 steps:

- Define the question of interest

- Get the data

- Clean the data

- Explore the data

- Fit statistical models

- Communicate the results

- Make your analysis reproducible

The reality is that the process is usually much more iterative. This is an excellent diagram describing the usual flow of a data science project by a former student in this class, Simina Boca:

Feeling preeety good about this diagram that I wrote in sparkly pens for the data analysis class I'm teaching, which starts tomorrow… Hope it's clear now that data scientists and applied statisticians don't simply press a 🖱️or wave a 🪄! Feedback welcome for future iterations! pic.twitter.com/BoDeyUuNvT

— Simina M. Boca (@siminaboca) August 27, 2020

A good data science project answers a real scientific or business analytics question. In almost all of these experiments the vast majority of the analyst’s time is spent on getting and cleaning the data (steps 2-3) and communication and reproducibility (6-7). In most cases, if the data scientist has done her job right the statistical models don’t need to be incredibly complicated to identify the important relationships the project is trying to find. In fact, if a complicated statistical model seems necessary, it often means that you don’t have the right data to answer the question you really want to answer. As Tukey said:

The combination of some data and an aching desire for an answer does not ensure that a reasonable answer can be extracted from a given body of data.

One option is to spend a huge amount of time trying to tune a statistical model to try to answer the question but serious data scientist’s usually instead try to go back and get the right data.

The result of this process is that most well executed and successful data science projects don’t (a) use super complicated tools or (b) fit super complicated statistical models. The characteristics of the most successful data science projects I’ve evaluated or been a part of are: (a) a laser focus on solving the scientific problem, (b) careful and thoughtful consideration of whether the data is the right data and whether there are any lurking confounders or biases and (c) relatively simple statistical models applied and interpreted skeptically.

2.2.2 Data Science is hard, but not like math is hard

It turns out doing those three things is actually surprisingly hard and very, very time consuming. It is my experience that data science projects take a solid 2-3 times as long to complete as a project in theoretical statistics. The reason is that inevitably the data are a mess and you have to clean them up, then you find out the data aren’t quite what you wanted to answer the question, so you go find a new data set and clean it up, etc. After a ton of work like that, you have a nice set of data to which you fit simple statistical models and then it looks super easy to someone who either doesn’t know about the data collection and cleaning process or doesn’t care.

This poses a major public relations problem for serious data scientists. When you show someone a good data science project they almost invariably think “oh that is easy” or “that is just a trivial statistical/machine learning model” and don’t see all of the work that goes into solving the real problems in data science. A concrete example of this is in academic statistics. It is customary for people to show theorems in their talks and maybe even some of the proof. This gives people working on theoretical projects an opportunity to “show their stuff” and demonstrate how good they are. The equivalent for a data scientist would be showing how they found and cleaned multiple data sets, merged them together, checked for biases, and arrived at a simplified data set. Showing the “proof” would be equivalent to showing how they matched IDs. These things often don’t look nearly as impressive in talks, particularly if the audience doesn’t have experience with how incredibly delicate real data analysis is. I imagine versions of this problem play out in industry as well (candidate X did a good analysis but it wasn’t anything special, candidate Y used Hadoop to do BIG DATA!).

The really tricky twist is that bad data science looks easy too. You can scrape a data set off the web and slap a machine learning algorithm on it no problem. So how do you judge whether a data science project is really “hard” and whether the data scientist is an expert? Just like with anything, there is no easy shortcut to evaluating data science projects. You have to ask questions about the details of how the data were collected, what kind of biases might exist, why they picked one data set over another, etc. In the meantime, don’t be fooled by what looks like simple data science - it can often be pretty effective.

This course is designed for PhD students in Biostatistics and most of the courses you have taken have been hard by virtue of mathematical difficulty. These courses focus on deductive resasoning whereby you are told a set of principles or facts and you deduce logically some conclusions through proofs. The steps may be tricky and may require deep mathematical understanding. But the important point is that there is a right answer to most of these problems.

Data science is much more akin to inductive reasoning. Inductive reasoning involves taking a small set of representative examples (say a sample of data) and trying to generalize these examples to make a broader statement (say a population). Even when the data are correct, the conculions you may draw can be wildly inaccurate. So the hard thing about data science is describing a path from a set of known data to a set of conclusions that can be supported by the data. Ideally, these conclusions will hold up to scrutiny, skepticism, and replication. In other words, data science is hard precisely because there is often not a “right” answer.

Good data science is distinguished from bad data science primarily by a repeatable, thoughtful, skeptical application of an analytic process to data in order to arrive at supportable conclusions.

2.2.3 So what is advanced data science?

Ask yourselves, what problem have you solved, ever, that was worth solving, where you knew knew all of the given information in advance? Where you didn’t have a surplus of information and have to filter it out, or you didn’t have insufficient information and have to go find some?

This quote comes from a Dan Meyer Ted Talk about patient problem solving. But it applies equally to data science.

Data science is answering questions with data and it requires a range of skills and therefore a range of classes:

- Level 0: Background: Basic computing, some calculus with a focus on optimization, basic linear algebra.

- Level 1: Data science thinking: How to define a question, how to turn a question into a statement about data, how to identify data sets that may be applicable, experimental design, critical thinking about data sets.

- Level 2: Data science communication: Teaching students how to write about data science, how to express models qualitatively and in mathematical notation, explaining how to interpret results of algorithms/models. Explaining how to make figures.

- Level 3: Data science tools: Learning the basic tools of R, loading data of various types, reading data, plotting data.

- Level 4: Real data: Manipulating different file formats, working with “messy” data, trying to organize multiple data sets into one data set.

- Level 5: Worked examples: Use real data examples, but work them through from start to finish as case studies, don’t make them easy clean data sets, but have a clear path from the beginning of the problem to the end.

- Level 6: Just the question: Give students a question where you have done a little research to know that it is posisble to get at least some data, but aren’t 100% sure it is the right data or that the problem can be perfectly solved. Part of the learning process here is knowing how to define success or failure and when to keep going or when to quit.

- Level 7: The student is the scientist: Have the students come up with their own questions and answer them using data.

As you move up the hierarchy of data science classes, the emphasis moves away from technological skills and toward synthesis and communication.

The hardest part of data science isn't the technology pic.twitter.com/2IslFWrJwa

— Caitlin Hudon 👩🏼💻 (@beeonaposy) August 26, 2020

This advanced data science course assumes you have background in statistics, programming, and the basics of project management - it will instead focus on synthesizing these tools into a data analysis and communicating the analysis to an audience.

We will instead focus on the “hard” part of data science, which is understanding the way to use data to make generalizable statements about the world and communicating those results to others.

Data analysis is often (incorrectly) distilled down to the set of claims or a whether a p-value is lower than some threshold. But the tip of this iceberg conceals a large number of analytic choices, human behaviors, biases, and conventions that underly the data analytic process.

This iceberg inspired the ADS 2020 course hex sticker. In this course we will focus on the parts of the data analysis that are often overlooked, but are critical to data analytic success.

2.3 Types of data analytic questions

Data can be used to answer many questions, but not all of them. One of the most innovative data scientists of all time said it best.

The data may not contain the answer. The combination of some data and an aching desire for an answer does not ensure that a reasonable answer can be extracted from a given body of data.

John Tukey

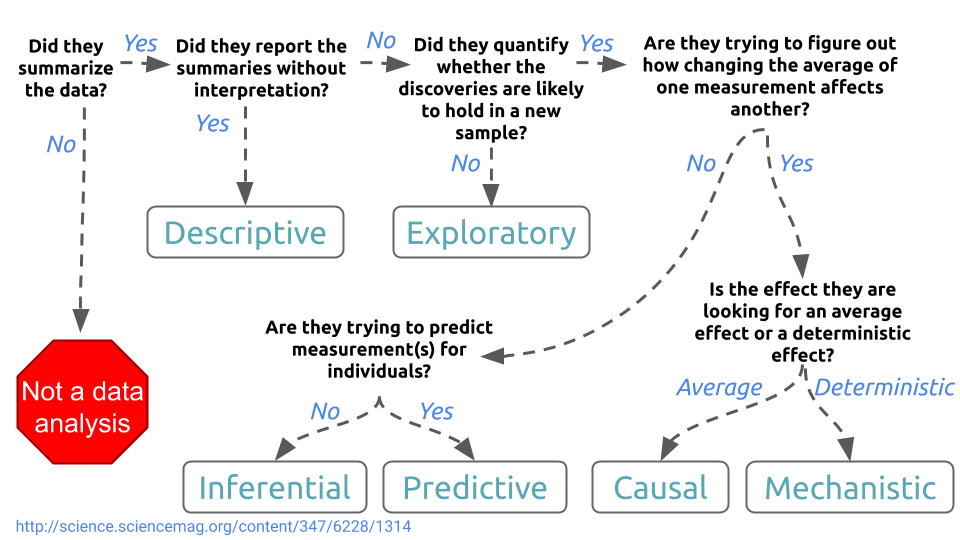

Before performing a data analysis the key is to define the type of question being asked. Some questions are easier to answer with data and some are harder. This is a broad categorization of the types of data analysis questions, ranked by how easy it is to answer the question with data. You can also use the data analysis question type flow chart to help define the question type (from the paper What is the question )

The data analysis question type flow chart

2.3.1 Descriptive

A descriptive data analysis seeks to summarize the measurements in a single data set without further interpretation. An example is the United States Census. The Census collects data on the residence type, location, age, sex, and race of all people in the United States at a fixed time. The Census is descriptive because the goal is to summarize the measurements in this fixed data set into population counts and describe how many people live in different parts of the United States. The interpretation and use of these counts is left to Congress and the public, but is not part of the data analysis.

2.3.2 Exploratory

An exploratory data analysis builds on a descriptive analysis by searching for discoveries, trends, correlations, or relationships between the measurements of multiple variables to generate ideas or hypotheses. An example is the discovery of a four-planet solar system by amateur astronomers using public astronomical data from the Kepler telescope. The data was made available through the planethunters.org website, that asked amateur astronomers to look for a characteristic pattern of light indicating potential planets. An exploratory analysis like this one seeks to make discoveries, but rarely can confirm those discoveries. In the case of the amateur astronomers, follow-up studies and additional data were needed to confirm the existence of the four-planet system.

2.3.3 Inferential

An inferential data analysis goes beyond an exploratory analysis by quantifying whether an observed pattern will likely hold beyond the data set in hand. Inferential data analyses are the most common statistical analysis in the formal scientific literature. An example is a study of whether air pollution correlates with life expectancy at the state level in the United States. The goal is to identify the strength of the relationship in both the specific data set and to determine whether that relationship will hold in future data. In non-randomized experiments, it is usually only possible to observe whether a relationship between two measurements exists. It is often impossible to determine how or why the relationship exists - it could be due to unmeasured data, relationships, or incomplete modeling.

2.3.4 Predictive

While an inferential data analysis quantifies the relationships among measurements at population-scale, a predictive data analysis uses a subset of measurements (the features) to predict another measurement (the outcome) on a single person or unit. An example is when organizations like FiveThirtyEight.com use polling data to predict how people will vote on election day. In some cases, the set of measurements used to predict the outcome will be intuitive. There is an obvious reason why polling data may be useful for predicting voting behavior. But predictive data analyses only show that you can predict one measurement from another, they don’t necessarily explain why that choice of prediction works.

2.3.5 Causal

A causal data analysis seeks to find out what happens to one measurement if you make another measurement change. An example is a randomized clinical trial to identify whether fecal transplants reduces infections due to Clostridium dificile. In this study, patients were randomized to receive a fecal transplant plus standard care or simply standard care. In the resulting data, the researchers identified a relationship between transplants and infection outcomes. The researchers were able to determine that fecal transplants caused a reduction in infection outcomes. Unlike a predictive or inferential data analysis, a causal data analysis identifies both the magnitude and direction of relationships between variables.

2.3.6 Mechanistic

Causal data analyses seek to identify average effects between often noisy variables. For example, decades of data show a clear causal relationship between smoking and cancer. If you smoke, it is a sure thing that your risk of cancer will increase. But it is not a sure thing that you will get cancer. The causal effect is real, but it is an effect on your average risk. A mechanistic data analysis seeks to demonstrate that changing one measurement always and exclusively leads to a specific, deterministic behavior in another. The goal is to not only understand that there is an effect, but how that effect operates. An example of a mechanistic analysis is analyzing data on how wing design changes air flow over a wing, leading to decreased drag. Outside of engineering, mechanistic data analysis is extremely challenging and rarely undertaken.

2.4 A data analytic rubric

There is often no “right” or “wrong” answer when evaluating a data analysis, but there are some characteristics that separate good analyses from poor analyses. One difficult thing about advanced data science is that these rules have not been formally defined like much of our statistical theory and are not generally agreed on. We are only at the beginning of developing a “theory” of data analysis - we will learn more about these efforts later in the class.

You can think of the theory of data analysis more like guidance than hard and fast rules. Roger Peng outlines this idea in his Dean’s lecture which I would encourage you to watch (the key analogy to music begins around 27 minutes in).

For now we will use a basic checklist (adapted from the book Elements of Data Analytic Style) when reviewing data analyses. It can be used as a guide during the process of a data analysis, as a rubric for grading data analysis projects, or as a way to evaluate the quality of a reported data analysis. You don’t have to answer every one of these questions for every data analysis, but they are a useful set of ideas ot keep in the back of your mind when reviewing a data analysis.

2.4.1 Answering the question

- Did you specify the type of data analytic question (e.g. exploration, association causality) before touching the data?

- Did you define the metric for success before beginning?

- Did you understand the context for the question and the scientific or business application?

- Did you record the experimental design?

- Did you consider whether the question could be answered with the available data?

2.4.2 Checking the data

- Did you plot univariate and multivariate summaries of the data?

- Did you check for outliers?

- Did you identify the missing data code?

2.4.3 Tidying the data

- Is each variable one column?

- Is each observation one row?

- Do different data types appear in each table?

- Did you record the recipe for moving from raw to tidy data?

- Did you create a code book?

- Did you record all parameters, units, and functions applied to the data?

2.4.4 Exploratory analysis

- Did you identify missing values?

- Did you make univariate plots (histograms, density plots, boxplots)?

- Did you consider correlations between variables (scatterplots)?

- Did you check the units of all data points to make sure they are in the right range?

- Did you try to identify any errors or miscoding of variables?

- Did you consider plotting on a log scale?

- Would a scatterplot be more informative?

2.4.5 Inference

- Did you identify what large population you are trying to describe?

- Did you clearly identify the quantities of interest in your model?

- Did you consider potential confounders?

- Did you identify and model potential sources of correlation such as measurements over time or space?

- Did you calculate a measure of uncertainty for each estimate on the scientific scale?

2.4.6 Prediction

- Did you identify in advance your error measure?

- Did you immediately split your data into training and validation?

- Did you use cross validation, resampling, or bootstrapping only on the training data?

- Did you create features using only the training data?

- Did you estimate parameters only on the training data?

- Did you fix all features, parameters, and models before applying to the validation data?

- Did you apply only one final model to the validation data and report the error rate?

2.4.7 Causality

- Did you identify whether your study was randomized?

- Did you identify potential reasons that causality may not be appropriate such as confounders, missing data, non-ignorable dropout, or unblinded experiments?

- If not, did you avoid using language that would imply cause and effect?

2.4.8 Written analyses

- Did you describe the question of interest?

- Did you describe the data set, experimental design, and question you are answering?

- Did you specify the type of data analytic question you are answering?

- Did you specify in clear notation the exact model you are fitting?

- Did you explain on the scale of interest what each estimate and measure of uncertainty means?

- Did you report a measure of uncertainty for each estimate on the scientific scale?

2.4.9 Figures

- Does each figure communicate an important piece of information or address a question of interest?

- Do all your figures include plain language axis labels?

- Is the font size large enough to read?

- Does every figure have a detailed caption that explains all axes, legends, and trends in the figure?

2.4.10 Presentations

- Did you lead with a brief, understandable to everyone statement of your problem?

- Did you explain the data, measurement technology, and experimental design before you explained your model?

- Did you explain the features you will use to model data before you explain the model?

- Did you make sure all legends and axes were legible from the back of the room?

2.4.11 Reproducibility

- Did you avoid doing calculations manually?

- Did you create a script that reproduces all your analyses?

- Did you save the raw and processed versions of your data?

- Did you record all versions of the software you used to process the data?

- Did you try to have someone else run your analysis code to confirm they got the same answers?

2.4.12 R packages

- Did you make your package name “Googleable”

- Did you write unit tests for your functions?

- Did you write help files for all functions?

- Did you write a vignette?

- Did you try to reduce dependencies to actively maintained packages?

- Have you eliminated all errors and warnings from R CMD CHECK?

2.5 Your first assignment - deconstructing an analysis

Before we leap into doing data analysis we are going to deconstruct some data analyses to help us discover what are the parts that work and don’t in different contexts. Your first assignment will be to read this data analysis about Mortality in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria. You will answer a series of questions, then we will discuss the analysis during class.

- Write a brief one paragraph summary of the paper highlighting what you consider to be the key parts of the analysis.

- Who you think the target audience of this paper is?

- What kind of question (descriptive, exploratory, inferenential, predictive, casual, or mechanistic) is this paper trying to answer?

- What is the main question the paper is trying to answer?

- Do you think the data used in the paper are sufficient to answer the question?

- What are the main sections of the paper? How do they support (or not) the answer to the question?

- Do you think the analytic methods (plots, summaries, statistical models) are sufficient to answer the question? Do you think it could have been done with simpler methods?

- Do you think you could reproduce this analysis based on the text? Do you have access to the data, the code, enough of a description of what happened? Why or why not?

- Do you think that the analysis was done in the order shown in the paper? Do you think the authors only did the analysis shown in the paper?

- Do you think that the overall analysis makes a convincing point? Why or why not?

2.6 Additional Resources

- The Elements of Data Analytic Style {data analysis book}

- The Art of Data Science {data analysis book}

- Advanced Data Analysis from an Elementary Point of View {methods book}

- An Introduction to Statistical Learning {methods book}

2.7 Homework

- Template Repo: https://github.com/advdatasci/homework1

- Repo Name: homework1-ind-yourgithubusername

- Pull Date: 2020/09/07 9:00AM Baltimore Time