15 Week 14

15.1 Week 14 Learning objectives

At the end of this lesson you will be able to:

- Define the types of relationships you will have as a data scientist

- Know how to be a helpful “data science reviewer”

- Understand and apply a transactional model for consulting relationships

- Understand how to find and maintain good collaborative relationships

15.2 What does collaboration mean?

Collaboration comes up often when you are a data scientist. Both in academic and industrial data science, it is crucial to understand the data you are using deeply. Sometimes that understanding will be from long, personal experience and you can accomplish projects on your own. More often, it is more efficient to work with people who have experience you don’t.

Collaboration between a data scientist and a subject matter expert can happen on a number of different levels. They range from a brief review of a few plots to a multi-year, deep relationship. The most common types of collaboration between a data scientist and a subject matter expert are:

- Reviewing relationship: The most cursory collaborative relationship for a data scientist is when you are simply reviewing the data or computational work that someone else did. You may not may not understand the subject matter and are only doing a technical review.

- Consulting relationship: A consulting relationship is one where you are typically being paid to work as a data scientist and provide only technical expertise on a project. Consulting can either be a short term relationship or a longer term relationship; but is typically one where you will not make a deep investment in the application area - you are typically involved for financial reasons.

- Collaborative relationship: A collaborative relationship is one where you are a part of a team working together to solve a common task. The relationship may involve a financial relationship, but will also involve a common scientific or business interest. True collaborative relationships are very rarely built over the short term; like good friendships they may take years to fully develop.

In general, the most rewarding experiences for data scientists tend to be in the collaborative category. They involve a mutually respectful symbiosis where you will learn a lot about the area of application and they will learn a lot about technical or computational tools from you. This doesn’t mean that the other types of relationships can’t be productive! It is much more scalable to simply review other’s computational work, when that work is performed by well-versed amateurs in data analysis. Consulting can be a great way to test the waters in new areas where you aren’t certain you want to work long term. Moreover, relationsihps can move back and forth between these categories over time.

15.3 The reviewing relationship

The reviewing relationship does not refer to peer review or acting as a formal referee. Rather it is the relationship between a data scientist and a colleague who wants you to look over their application of data science to ensure the accuracy of their work. This type of relationship might be as brief as a couple of emails or might last through the entire creation of a paper or product. When you are the reviewer

As a reviewer your job is to look over other people’s work and provide feedback on ways that it could be improved or corrected. When you take on this role, you aren’t committing significant time or effort to understand the application area - rather you are concerned very specifically with the quality of the data analytic work that was performed.

Some important do’s and don’t for a reviewing relationship are:

15.3.1 Do

- Be respectful and considerate. Constructive criticism is much more likely to be accepted and used. It is also helpful to have empathy and consider that there is a person asking for feedback, not a robot. Keep that in mind particularly when providing difficult or negative feedback.

- Be aware that you don’t know all of the details. You are an expert in data analytic techniques, but may not understand the nuances of the application in question. Keep your feedback focused within your area of expertise.

- Be specific. A reviewing relationship is necessarily more lightweight and you won’t have time to have a deep conversation. Specific feedback (“increase your sample size by 5 in each group”, “split your data into training, testing, and validatioN”) is easier to act on than vague feedback (“you don’t have a big enough sample size”, “your study design won’t work for this problem”)

- Be aware of project stage. If you are reviewing a project proposal there is still a lot of latitute to change things. If you come in at the end, only minor tweaks may still be possible. Keep that in mind and provide feedback that is actionable for the project stage.

15.3.2 Don’t

- Become the data scientist. If you are just reviewing data analytic work of someone else and you aren’t in a formal consulting or collaborative relationship, avoid the temptation to simply “redo” the analysis, even if it would be easy for you.

- Be unnecessarily critical or rude. The golden rule still applies to reviewing. In particular, you may be brought in when a project is nearly complete and you may have serious reservations about the quality of the data analytic work. But avoid the temptation to do a “post-mortem” on their data and ideas.

- Avoid the truth. Although your goal is to be empathetic and polite, it is important that you give real feedback. If someone comes to you for technical help or support and you avoid pointing out flaws in their approach to be polite, you are setting them up for failure in the long run. Frank Harrell has a nice checklist of potential statistical issues to look out for.

15.4 The consulting relationship

A consulting relationship is a transactional data science relationship. Sometimes this transaction is really formal, for example we have a Biostatistics Consulting Center that works with scientists and doctors all across the Johns Hopkins Institutions. These typically involve a system where the data scientist or (bio)statistician are paid per hour or per project to perform data analysis for a scientific colleague.

Consulting relationships are significantly more involved than reviewing relationships. You are usually doing data analytic work, writing code, writing manuscripts, and providing support for your clients. Consulting is sometimes formalized with specific contracts of dollars per hour. It may also be less formal, if you work for a company with a data science group, you may support different “functional units” within a company.

Consulting may last only a week or two, or may be a multi-year effort. The longer the relationship goes on, the more you will learn about the subject matter you are studying. Eventually you may be involved in the scientific decisions, but often that won’t be your role. Instead, you will be analyzing the data to arrive at answers driven by the questions of your clients.

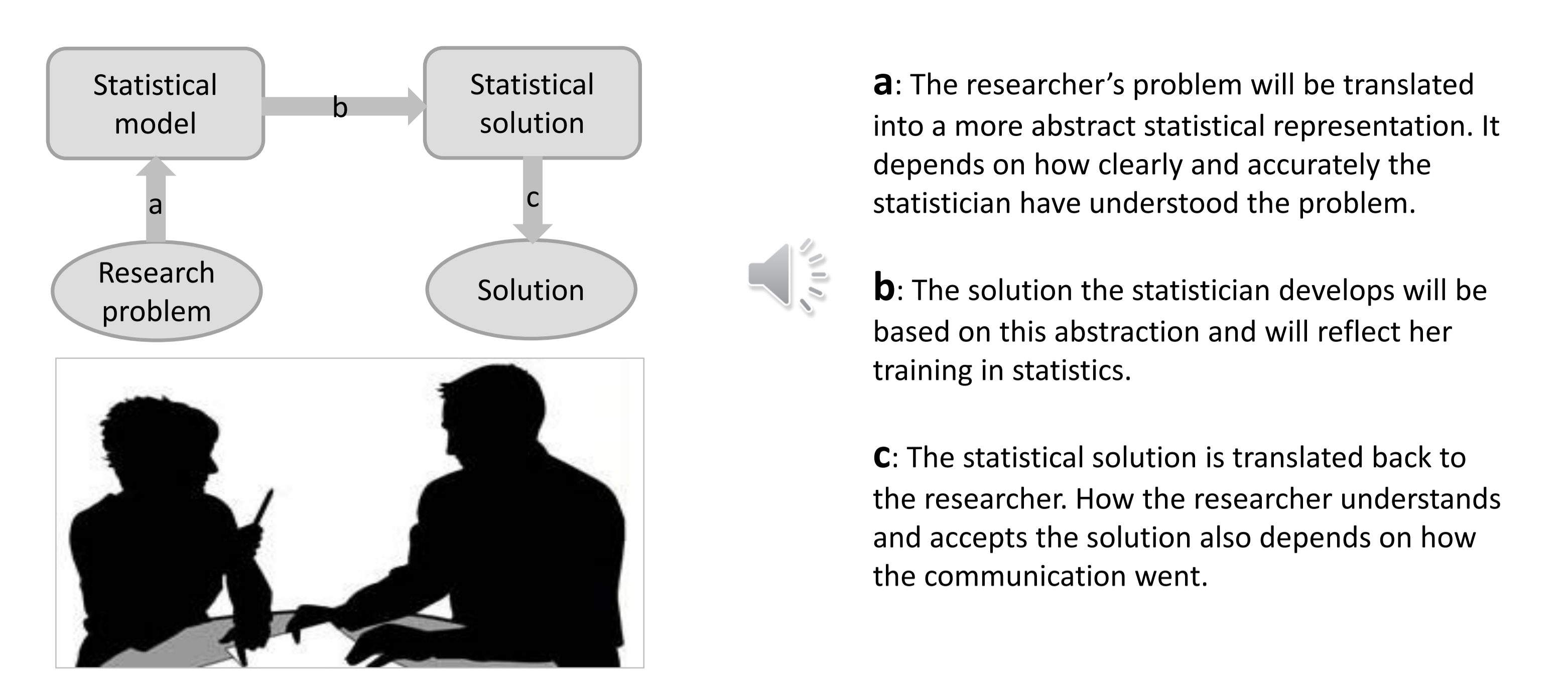

Jiangxia Wang has some very nice slides on statistical consulting as she very nicely puts it the role of the statistical consultant has three components: (a) translating scientific questions into statistical questions, (b) applying statistical modeling to the data to resolve the statistical question, and (c) translating the statistical answers back into scientific terms.

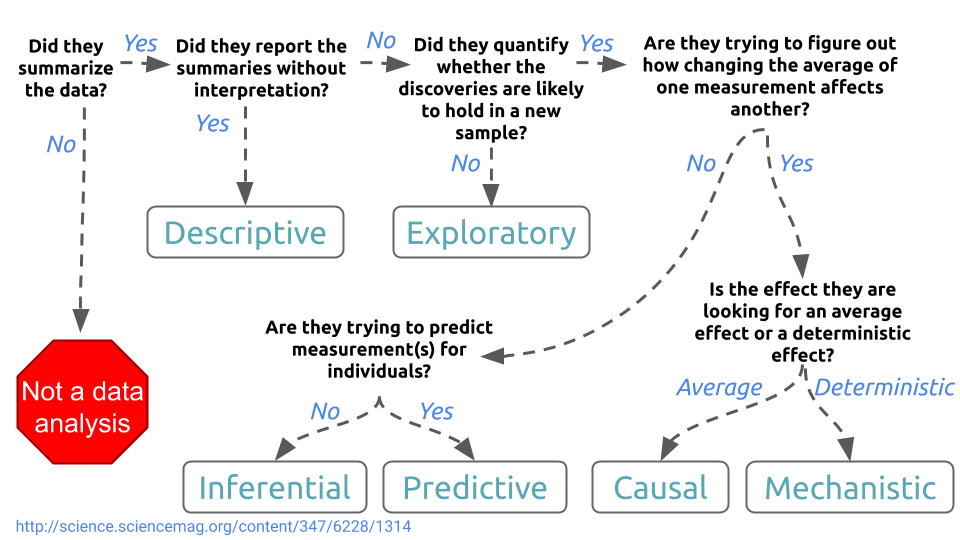

This process is often elicited via an interactive interview where you will need to investigate what the scientific goals are and match them to a statistical model, then confirm that you have matched expectations. It can be really useful to take clients through the question defining flowchart we discussed in Week 1:

There are also some unique challenges that come with the consulting relationship.

15.4.1 What am I paying you for?

For one, you are being paid to analyze data for someone. They will have incentives that may or may not align with the results of your data analysis. A key challenge for anyone analyzing data, no matter the relationship, is that the data will say what they say. It may or may not match you or your client’s hopes. If the results don’t come out as expected, you may be pressured to produce results your client likes better.

The pressure to find results may be explicit or it may be implicit - but it is extremely common to feel this kind of pressure. When you do, it is important to clearly document what you have found and provide the best advice you can. It can be helpful to enlist other data scientists who are more senior than you to help validate your work, especially if there is a power differential between you and your client.

15.4.3 But this is just so important for science…

It is common for statistics, data analysis, and data science to be underfunded relative to data collection in collaborative projects in data science. It is a common experience to have a consulting client to get you to work for free or at a very low cost due to the importance of a project. In collaborative relationships this is possibly ok, but in consulting relationships where it is a transactional experience, it is much more important to stand up for yourself and set clear boundaries around what you are willing to commit in terms of time and effort and what you expect in return. Otherwise, you will be a very popular, and very burned out data scientist.

15.4.4 This should be really quick

At times when working with people who haven’t done much data analysis before, they might misunderstand how long it will take to do an analysis. For example, they may send you a gnarly Excel file that takes several hours to disentangle and tidy before you can perform a simple regression model. While the regression model might take 5 minutes to run, the total project could be hours long. You may get pressure to turn things around much faster than is possible - clients may ask for analysis of a data set that took years to collect in a day or two. You may also run into situations where your time isn’t correctly calibrated and valued. This is a situation where it is helpful to set expectations in advance and to be conservative, building in time for the unexpected into any estimates you give for how long it will take you to complete an analysis. It is also useful to communicate up front how you will respond, on what time frame you can do the analysis, and to consistently provide updates as you progress about any deviations from the plan. Again, if you are in a relationship where there is a power differential, it can be useful to reach out to a more senior data analytic colleague to support you when you explain the real challenges in performing good data scientific work.

To summarize here are some of the do’s and don’ts for a consulting relationship.

15.4.5 Do

- Communicate clearly about expectations. Be clear about financial commitments, time commitments, and what is involved in the consulting exchange. It can feel uncomfortable, but it is better to set expectations in advance.

- Treat your time and expertise as valuable. Since you are the expert in data analysis, it is up to you to set realistic and clear expectations for how long things will take and what is and isn’t possible.

- Communicate often. Consulting relationships involve a lot of projections - how long something will take, which techniques might work, how much it will cost. It is ok if these projections change, but it is important to be up front about these potential changes, rather than communicate them post-hoc.

- Treat your client with respect. They are coming to you for your help in data analysis, but they are much more expert in their area of focus. Respect their knowledge and use it as an opportunity to ask them lots of questions and learn about a new field.

15.4.6 Don’t

- Forget the relationship is transactional. A consulting relationship is meant to be transactional. That doesn’t mean adversarial! It can be really positive for both parties. But it does mean that you should be clear about finances, time, credit, and any other exchange that is going to happen up front.

- Allow yourself to be pressured to do dishonest analysis. When doing data analysis as a consultant, there will almost always be motivation from your client to find a certain result. Your job is to report clearly what you find. They may choose to use those results in ways you don’t agree with, but the data analysis itself that you hand over should reflect your best understanding of the data.

- Work for less than you are worth. If people don’t understand your expertise, they may be tempted to try to devalue your work and compensate you in terms of credit or money with less than you are worth. Talk to colleagues, evaluate carefully, and pick projects that give you a fair deal.

Consulting relationships may stay purely transactional, or you may find yourself getting more interested by the business or scientific application and the relationship could deepen into a collaboration.

15.5 The collaborative relationship

A collaboration is a scientific or business relationship where you work with others on an area of common scientific interest. It is distinguished from a consulting relationship in that you typically have some skin in the game. You may be co-leaders on a project, you may help to design and analyze experiments together, you may brainstorm new projects. These are the types of relationships that can be most rewarding if you really commit to them. But collaboration, like any relationship, takes time to develop and needs effort to be really fulfilling.

15.5.1 Finding Good Collaborators

This section is borrowed with very slight modification from Roger’s excellent post on this topic.

The job of the data scientist is often about collaboration. Sure, there’s theoretical work that we can do by ourselves, but most of the impact that we have on science comes from our work with scientists in other fields. Collaboration is also what makes the field of data science so much fun.

A question you might ask is “how do you find good collaborations”? Or, put another way, how do you find good collaborators? It turns out this distinction is more important than it might seem.

One strategy for finding good collaborations is to look for good collaborators. It is important to work with people that you like as well as respect as scientists, because a good collaboration is going to involve a lot of personal interaction. A place like Johns Hopkins has no shortage of very intelligent and very productive researchers that are doing interesting things, but that doesn’t mean you want to work with all of them.

Here is some general advice about finding good collaborations:

- Find people you can work with. Sometimes a data scientist will want to work with someone because he/she is working on an important problem. Of course, you want to be working on a problem that interests you, but it’s only partly about the specific project. It’s very much about the person. If you can’t develop a strong working relationship with a collaborator, both sides will suffer. If you don’t feel comfortable asking (stupid) questions, pointing out problems, or making suggestions, then chances are the science won’t be as good as it could be.

- It’s going to take some time. I sometimes half-jokingly tell people that good collaborations are what you’re left with after getting rid of all your bad ones. Part of the reasoning here is that you actually may not know what kinds of people you are most comfortable working with. So it takes time and a series of interactions to learn these things about yourself and to see what works and doesn’t work. Of course, you can’t take forever, particularly in academic settings where the tenure clock might be ticking, but you also can’t rush things either. One rule I heard once was that a collaboration is worth doing if it will likely end up with a published paper. That’s a decent rule of thumb, but see my next comment.

- It’s going to take some time. Developing good collaborations will usually take some time, even if you’ve found the right person. You might need to learn the science, get up to speed on the latest methods/techniques, learn the jargon, etc. So it might be a while before you can start having intelligent conversations about the subject matter. Then it takes time to understand how the key scientific questions translate to data science problems. Then it takes time to figure out how to develop new methods to address these data science problems. So a good collaboration is a serious long-term investment which has some risk of not working out. There may not be a lot of products initially, but the idea is to make the early investment so that truly excellent papers can be published later.

- Work with people who are getting things done. Nothing is more frustrating than collaborating on a project with someone who isn’t that interested in bringing it to a close (i.e. a published paper, completed software package). Sometimes there isn’t a strong incentive for the collaborator to finish (i.e she/he is already tenured) and other times things just fall by the wayside. So finding a collaborator who is continuously getting things done is key. One way to determine this is to check out their CV. Is there a steady stream of productivity? Papers in good journals? Software used by lots of other people? Grants? Web site that’s not in total disrepair?

- You’re not like everyone else. One thing that surprised me was discovering that just because someone you know works well with a specific person doesn’t mean that you will work well with that person. This sounds obvious in retrospect, but there were a few situations where a collaborator was recommended to me by a source that I trusted completely, and yet the collaboration didn’t work out. The bottom line is to trust your mentors and friends, but realize that differences in personality and scientific interests may determine a different set of collaborators with whom you work well.

15.5.2 Care and feeding of your collaborators

This section is borrowed with very slight modification from Roger’s excellent post on this topic. You may also want to check out Elizabeth Matsui’s corresponding post from the scientific side

Elizabeth and Roger Peng have been working for over half a decade and the story of how they started working together is perhaps a brief lesson on collaboration in and of itself. Basically, she emailed someone who didn’t have time, so that person emailed someone else who didn’t have time, so that person emailed someone else who didn’t have time, so that person emailed Roger, who as a mere assistant professor had plenty of time! A few people I’ve talked to are irked by this process because it feels like you’re someone’s fourth choice. But personally, I don’t care. I’d say almost all my good collaborations have come about this way. To me, it either works or it doesn’t work, regardless of where on the list you were when you were contacted.

Now that you’ve found this good collaborator, what do I do with her/him?

Understand that a scientist is not a fountain from which “the numbers” flow. Most data scientists like to work with data, and some even need it to demonstrate the usefulness of their methods or theory. So there’s a temptation to go “find a scientist” to “give you some data”. This is starting off on the wrong foot. If you picture your collaborator as a person who hands over the data and then you never talk to that person again (because who needs a clinician for an R package?), then things will probably not end up so great. There are two ways in which the experience will be sub-optimal. First, your scientist collaborator may feel miffed that you basically went off and did your own thing, making her/him less inclined to work with you in the future. Second, the product you end up with (paper, software, etc.) might not have the same impact on science as it would have had if you’d worked together more closely. This is the bigger problem: see #5 below.

All good collaborations involve some teaching. Be patient, not patronizing. Data scientists are often annoyed that “So-and-so didn’t even know this” or “they tried to do this with a sample size of 3!” True, there are egregious cases of scientists with a lack of basic statistical knowledge, but all good collaborations involve some teaching. Otherwise, why would you collaborate with someone who knows exactly the same things that you know? Just like it’s important to take some time to learn the discipline where you are analyzing data, it’s important to take some time to describe to your collaborator how those methods you’re using really work. Where does the information in the data come from? What aspects are important; what aspects are not important? What do parameter estimates mean in the context of this problem? If you find you can’t actually explain these concepts, or become very impatient when they don’t understand, that may be an indication that there’s a problem with the method itself that may need rethinking. Or maybe you just need a simpler method.

Go to where they are. This bit of advice Roger got from Scott Zeger when he was just starting out at Johns Hopkins. Scott’s bottom line was that if you understand where the data come from (as in literally, the data come from this organ in this person’s body), then you might not be so flippant about asking for an extra 100 subjects to have a sufficient sample size. In biomedical science, the data usually come from people. Real people. And the job of collecting that data, the scientist’s job, is usually not easy. So if you have a chance, go see how the data are collected and what needs to be done. Even just going to their office or lab for a meeting rather than having them come to you can be helpful in understanding the environment in which they work. I know it can feel nice (and convenient) to have everyone coming to you, but that’s crap. Take the time and go to where they are.

Their business is your business, so pitch in. A lot of research (and actually most jobs) involves doing things that are not specifically relevant to your primary goal (a paper in a good journal). But sometimes you do those things to achieve broader goals, like building better relationships and networks of contacts. This may involve, say, doing a sample size calculation once in a while for a new grant that’s going in. That may not be pertinent to your current project, but it’s not that hard to do, and it’ll help your collaborator a lot. You’re part of a team here, so everyone has to pitch in. In a restaurant kitchen, even the Chef works the line once in a while. Another way to think of this is as an investment. Particularly in the early stages there’s going to be a lot of ambiguity about what should be done and what is the best way to proceed. Sometimes the ideal solution won’t show itself until much later (the so-called “j-shaped curve” of investment). In the meantime, pitch in and keep things going.

Your job is to advance the science. In a good collaboration, everyone should be focused on the same goal. In my area, that goal is improving public health. If I have to prove a theorem or develop a new method to do that, then I will (or at least try). But if I’m collaborating with a biomedical scientist, there has to be an alignment of long-term goals. Otherwise, if the goals are scattered, the science tends to be scattered, and ultimately sub-optimal with respect to impact. I actually think that if you think of your job in this way (to advance the science), then you end up with better collaborations. Why? Because you start looking for people who are similarly advancing the science and having an impact, rather than looking for people who have “good data”, whatever that means, for applying your methods.

In the end, data scientists need to focus on two things: Go out and find the best people to work with and then help them advance the science.

15.5.3 A collaboration is a relationship

Roger and Elizabeth, who wrote the posts that a good fraction of this lecture is based on, coined a term collabofriends for collaborators who are also friends.

But collaborations, like any relationship, can go wrong. Just like with other relationships, this is often due to miscommunication, changing priorities, or lack of appropriate effort. They can also go wrong when one party starts to take advantage of the other in terms of time, effort, or finances. Communication is key, if you feel like you are in a difficult spot with a collaborator, it is best to be up front with them and work through the issue. It is also often helpful to realize that sometimes you will be getting the thing you most want out of the relationship and sometimes it will be your collaborators turn. This is typical relationship advice, but can be useful to keep in mind when having converations about authorship, credit, or funding.

15.8 Additional Resources

- The Care and Feeding of Your Scientist Collaborator

- The Care and Feeding of the Biostatistician

- Identifying bioethical issues in biostatistical consulting: findings from a US national pilot survey of biostatisticians

- Collaborating Reproducibly

- Collaborating with a Biostatistician - Best tips and practices

- A guide for the lonely bioinformatician

15.9 Homework

- Template Repo: https://github.com/advdatasci/homework14

- Repo Name: homework14-ind-yourgithubusername

- Pull Date: 2020/12/14 9:00AM Baltimore Time